Download the report in .pdf

English – Finnish

Author: Ville Manninen (University of Jyväskylä)

December, 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF. The data collection was carried out between May and October 2016.

In Finland, the CMPF partnered with Ville Manninen (University of Jyväskylä), who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annexe 2 for the list of experts).

To gather the voices of multiple stakeholders, the Finnish data collector organized a stakeholder meeting on 14.11.2016 in Helsinki. An overview of this meeting and a summary of the key points of discussion appear in the Annexe 3.

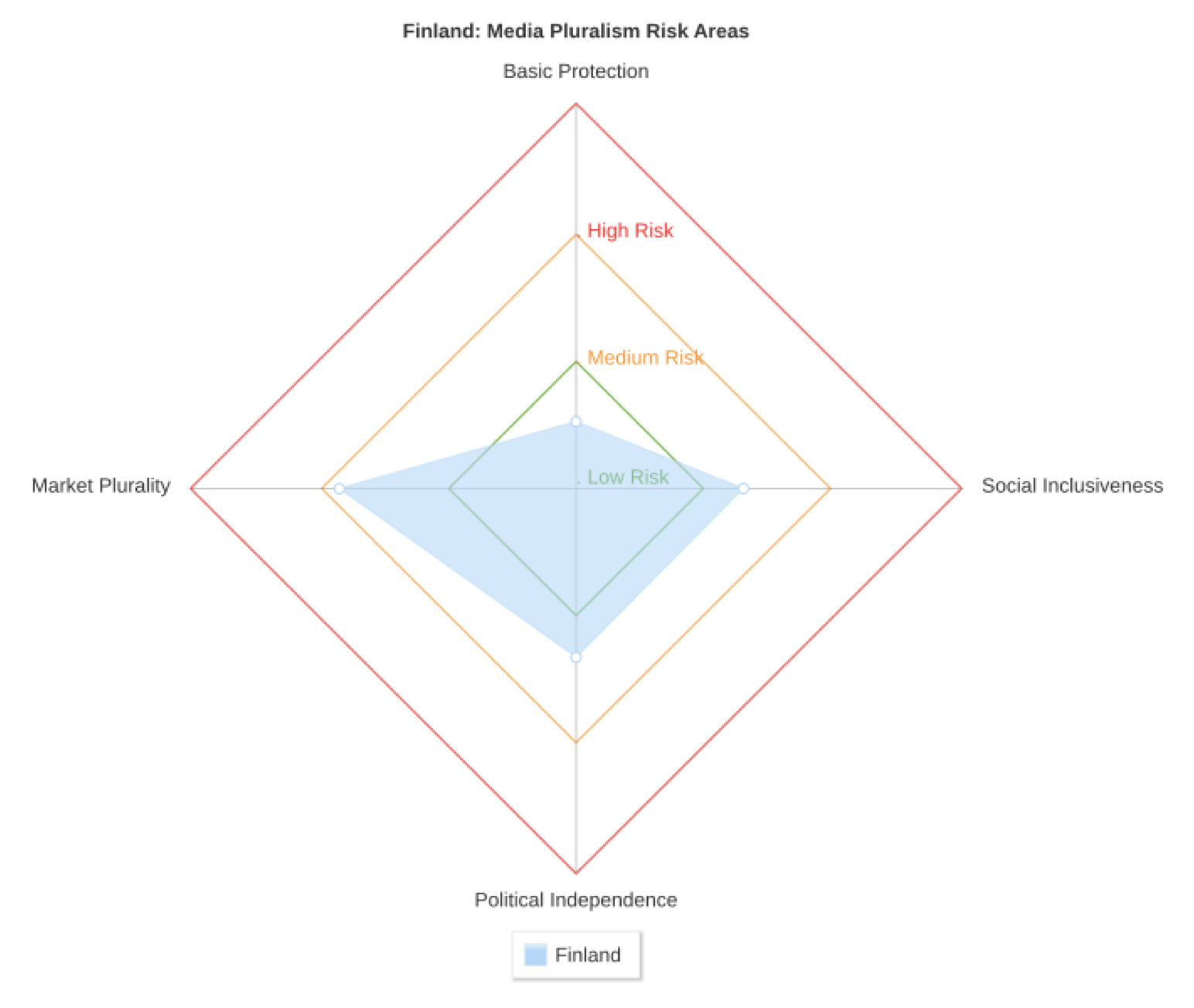

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Finland is a relatively large country (approx. 338,000 km2) with a small, largely urban, population (5.4 million). Notably, more than one-fifth of the population resides in the Helsinki metropolitan area, which has about 1.1 million residents.

Finland has two official languages, Finnish (89% of the population) and Swedish (5.3%). The law guarantees equal access to public services for speakers of both languages. In addition, the language of a small Sámi minority enjoys some legal privileges. Other lingual minorities do exist, the largest of which is Russian.

The population of Finland is relatively homogenous: 6.1% of the population was born outside of Finland, and 5.7% speak as their primary language something other than Finnish or Swedish.

Finland is among the world’s wealthier nations. Its per capita GDP (38,162 euros in 2015) is slightly above the EU average. Finland is, however, still recovering from the recession that began in 2008. The GDP growth rate has repeatedly dipped below zero since 2008 and has not exceeded 1.2% since 2011. Economic recovery is among the focal political issues of today.

For decades the Finnish political field was dominated by the trio of old, large parties skirted by a handful of smaller ones. Today, some smaller parties are closing the gap to the old hegemons. The power balance was for a long time tilted centre-left in most election cycles. The balance has shifted towards the centre-right in recent years, and nationalist-populist tones have emerged. The ruling three-party coalition holds 123 seats in the 200-seat parliament, with five parties in opposition.

The traditional characteristics of Finnish media are subscription-based, regional news dailies and a strong public service broadcaster (Yleisradio, or Yle). A handful of companies dominate the private radio and television markets, yet in terms of audience shares Yle remains unparalleled. The newspaper market is less concentrated due to a long history of locally owned small-town papers cum regionals. There is, however, an ongoing trend of conglomeration as papers in financial trouble are being bought by their larger neighbours. Most media companies have expanded or are expanding their operations online, but with limited financial success.

Roughly half of television viewers have cable services and the other half has terrestrial broadcasts, while satellite dishes remain marginal. Most Finns use the internet daily and the audience’s media consumption is rapidly shifting online. The total value of the Finnish mass media market was in 2015 approximately € 3.7 billion.

Finnish media is largely unregulated in terms of content. Radio and television programme licences impose some conditions. Adherence to them is monitored by the Finnish Communications Regulatory Authority. No major changes to media regulation have been made in recent years. In 2016, a parliamentary committee reassessed Yle’s remit and suggested, among other things, increasing the powers of the Parliament-appointed Administrative Council. None of the suggestions have, to date, been implemented.

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

Finland scores a low risk rating with regards to the basic legal protections of media freedom, but medium risk in all three other Monitor areas. The results are unexpected, as the state of Finnish media generally has not been publicly debated, apart from certain recurring topics such as the role and funding of public service media.

Most of the risk-increasing factors relate to the Finnish state’s overarching policy of non-interference: few legal controls have been imposed on media businesses or on the content they offer. This policy may be problematic for the various ethnic and societal minorities, whose de facto access to media remains limited without any support. However, the majority of Finnish media does not seem to be adversely affected by the lax regulation.

Other, occasional issues relate to articles of legislation, threats against journalists, and the relationship between the public service media corporation and the government. By and large, however, the Finnish media is free from outside pressures. Instead, it has to grapple with endemic problems such as declining revenues, a small and saturated market, and under-representation of financially unviable audiences.

Several individual indicators reach a high risk level. They relate to media market concentration, PSM independence, and access to media by marginal social groups. In many cases, research on the current situation and its social implications is not available. Therefore, it is unclear how harmful, or harmless, are the extant conditions. Thus, the medium risk results in some of the areas should be considered tentative, yet in part alarming.

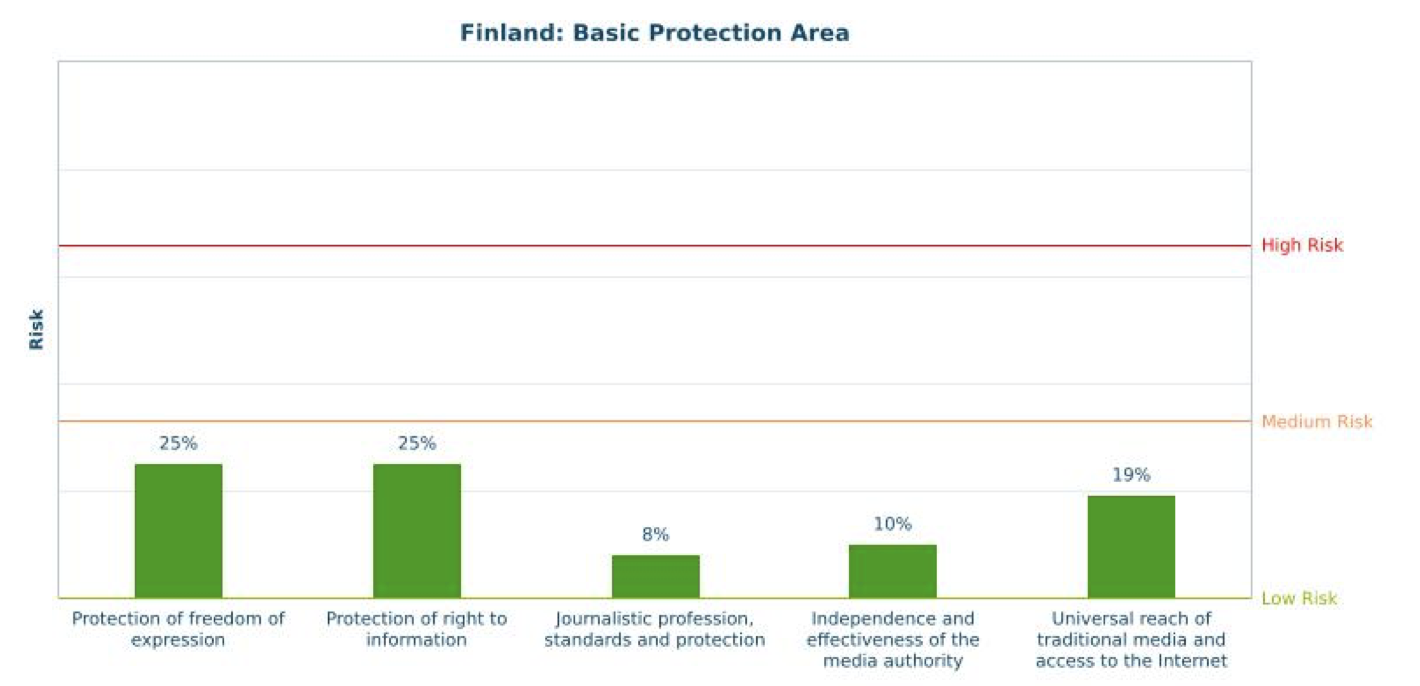

3.1. Basic Protection (17% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

The conditions in which Finnish media operate are among the most favourable in the world. Legal restrictions are scarce and freedom of speech is protected. There are, however, issues which set Finland apart from the ideal.

The indicator Protection of freedom of expression acquires a 25% risk score. This is due to the persistent criminalization of defamation and blasphemy. The relevant laws also feature wording which make the threshold to crime ambiguous and partially contingent on the victim’s subjective experience. The legislation also makes (aggravated) defamation punishable by up to two years imprisonment. The maximum sentence is practically never used, but its existence may be seen as a disproportionate deterrent.

The indicator on Protection of right to information (also acquires a 25% risk score) is weighed down by poor implementation of freedom of information legislation. Officials, through either ignorance or wilful negligence, occasionally deny access to information, which by law should be freely accessible. Overturning these unlawful decisions through appeals is slow, and the process, while deterring or hindering journalists, could form an insurmountable obstacle for a layperson.

Journalistic profession, standards and protection acquires one of the lowest risk scores (8%). Overall, working conditions of Finnish journalists are very permissive. Entry to the profession is unregulated; source confidentiality is effectively protected by law; journalists enjoy above-median pay; and most have stable employment. Unfortunately, threats and occasional physical attacks against journalists do occur.

The indicator Independence and effectiveness of the media authority acquires a 10% risk score. Even though Finland does not have a media authority per se, the Finnish Communications Regulatory Authority (Ficora) is considered to be a comparable institution. There are not any known problems within Ficora’s limited remit. However a portion (approximately 35%) of Ficora’s budget is allocated annually through the state budget. The Monitor considers this discretionary power over a part of the authority’s budget a potential threat to its independence.

Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet acquires a 19% risk score. Practically all Finns (>99%) live within the area covered by public service television and radio broadcasts. Almost all have access to some form of broadband internet connection (90% already have subscriptions and 99.8% live in areas where connections are available). Access to PSM and broadband internet connection are legal rights. This indicator’s risk score is elevated by the highly concentrated internet service provider (ISP) market: the four largest ISPs account for approximately 99 % of internet subscriptions.

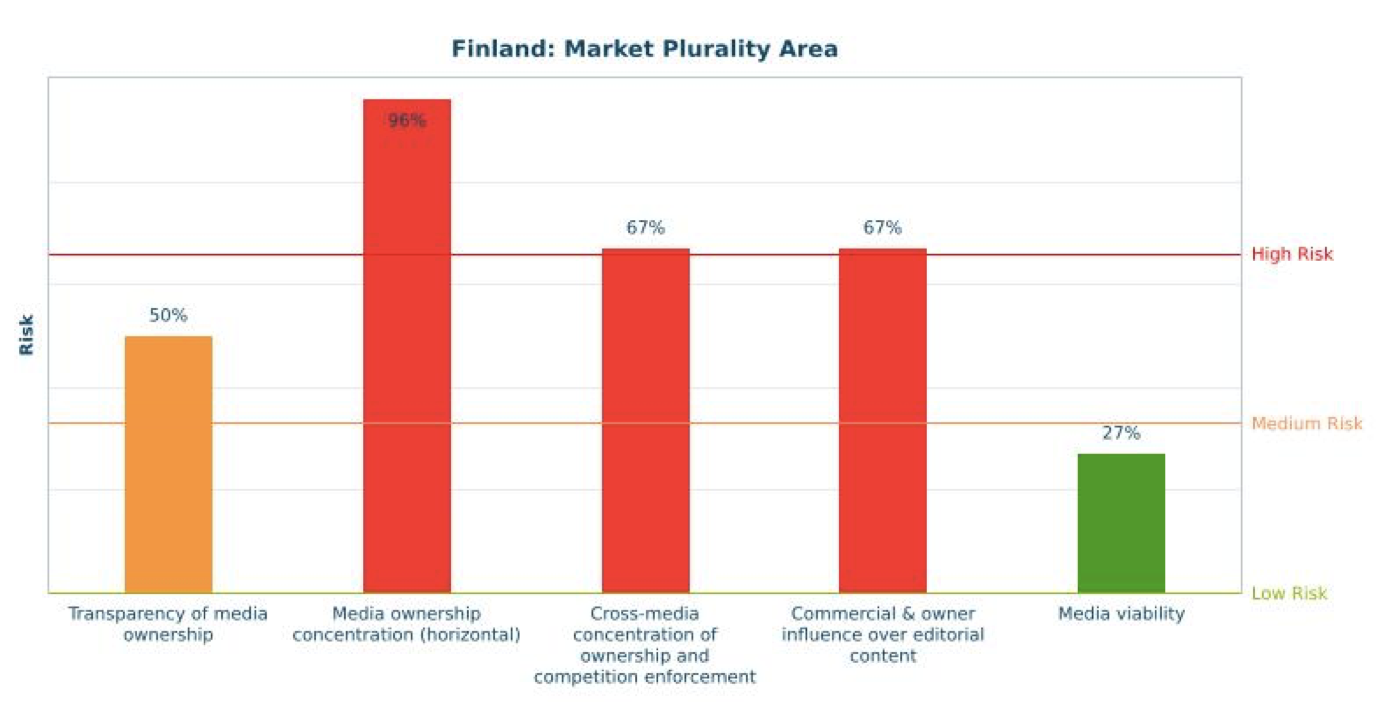

3.2. Market Plurality (61% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The Finnish media market is highly concentrated. This is in part due to the market’s small size and lingual isolation. Both infrastructure and workforce expenses are high, so the market can support only a limited number of companies with modern production capabilities, especially in the television and radio sectors. Finland has a long tradition of numerous local and regional newspapers, which continue to survive in large numbers. Still, expanding newspaper chains are a feature of Finland’s contemporary media market.

The indicator Transparency of media ownership acquires a 50% risk score. Finnish legislation does not set additional transparency requirements for media companies. This allows media owners to obfuscate their control by means of offshore holding companies if they so desire. Most media companies operating in Finland are by choice open about their ownership, but technically nothing prevents companies from hiding their true controllers even from the relevant authorities.

Horizontal ownership concentration acquires a 96% risk score, which is the highest for Finland. This is due to the few companies that dominate each media sector. In the TV broadcast sector, the four largest companies hold 92% of the audience and 97% of revenues; the four largest companies in the radio market hold 80% and 92%; and the four largest companies in the newspaper market hold 59% (audience) and 64% (revenue). There are no legal limits to media market concentration. General competition legislation applies to media companies, but its means and scope is geared toward facilitating competition, not plurality.

Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement acquires a 67% high risk score. Some of Finland’s largest media companies are active in two or more fields, and the four largest companies have 65% of the newspaper, television, radio, and online advertisement markets’ revenues. Finnish law does not prohibit this level of concentration, as long as it does not result in a situation which constricts effective competition.

The indicator Commercial & owner influence over editorial content also acquires a 67% high risk score. This type of influence rarely affects editorial content directly, but attempts are occasionally made. Small, local newspapers and certain lifestyle publications are more financially dependent on advertisers and they are more susceptible to commercial pressures. Finnish journalists highly value their independence, and they appear adamant on resisting outside influence on their work.

Media viability acquires a low 27% risk score. Revenues in both newspaper and television markets have in recent years been fluctuating in a manner that clearly indicates neither an overall increase nor decrease. The radio and online advertisement sectors, however, have seen increases in their revenues. Media companies are experimenting feverishly with new mechanisms of income generation. The Finnish state provides scant fiscal support for media, apart from funding the PSB and applying a lowered VAT rate to newspaper and magazine subscriptions. Some forms of direct subsidies exist, but they are very limited in size and eligibility.

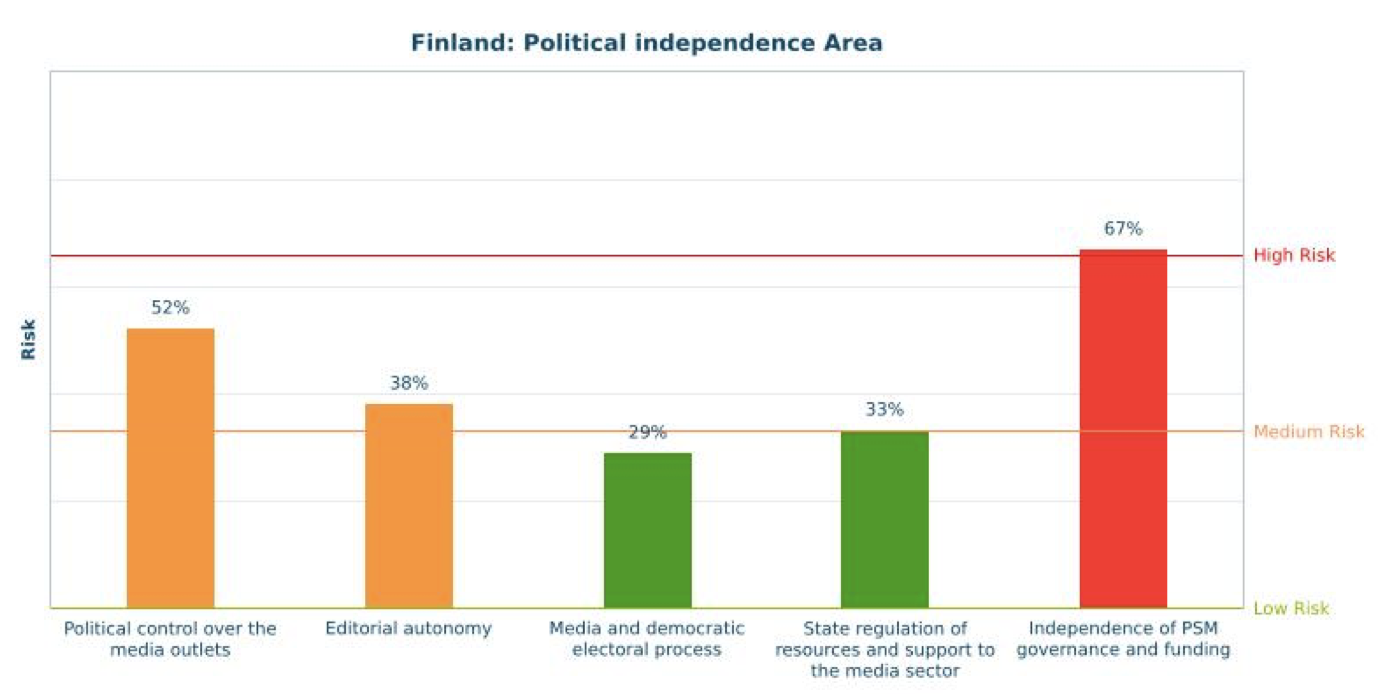

3.3. Political Independence (44% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

Finland’s legislation does not impose restrictions on politicized media ownership or content. Despite this, private media in Finland is largely independent from political parties, politicians, and other openly partisan actors. Most political parties do have some publishing activities, but the partisan media have practically no audience beyond the parties’ own memberships. The PSM is overseen by both the Finnish Communications Regulatory Authority and the national Parliament. The indicator Political control over the media outlets acquires a medium 52% risk score. The issue here is that no law prohibits political or politicized control of media outlets.

The indicator on Editorial autonomy scores a medium 38% risk level, which is caused by two factors. First, a law prohibiting political influence in hiring or firing of editors does not exist – although nothing suggests this would currently be a widespread practice in Finland. Second, there is some evidence that indirect political influence can sometimes reflect on news media. Based on journalists’ assessments, however, the extent of this influence appears to be a minor concern. Nevertheless, conclusive and recent research on the subject is not available.

Media and democratic electoral process acquires a low 29% risk score. The risk is caused by the lack of legislation that would compel media outlets (both private and public service) to treat all political parties equally and grant them access to media prior to elections. Despite the lack of regulation, there is little evidence of media treating parties unevenly. It should be noted, however, that no recent research on parties’ media representations exists, and that some allegations of media bias have been raised.

State regulation of resources and support to the media sector has a low 33% risk score, which borders with medium risk. The risk here comprises the state’s scant financial support to media and the opaque way the few direct subsidies are distributed: The criteria according to which funding decisions are made is not public, and in part the funding is consistently and disproportionately awarded to particular applicants year after year.

The indicator on Independence of PSM governance and funding acquires a high 67% risk score. The risk is because the PSM Yle is not legally insulated from political power: its highest governing body is appointed by (and traditionally from among) the members of the national Parliament. Political parties also have a long history of influencing appointments of Yle’s Director General. Despite efforts in recent years to distance the appointments from politics, even more recent appointments have been criticised as being political. Representatives of Yle claim the corporation’s daily operations are protected from political influence by organisational “firewalls”. Thus it is possible (although difficult to verify) that Yle’s daily functions are practically free from political influence.

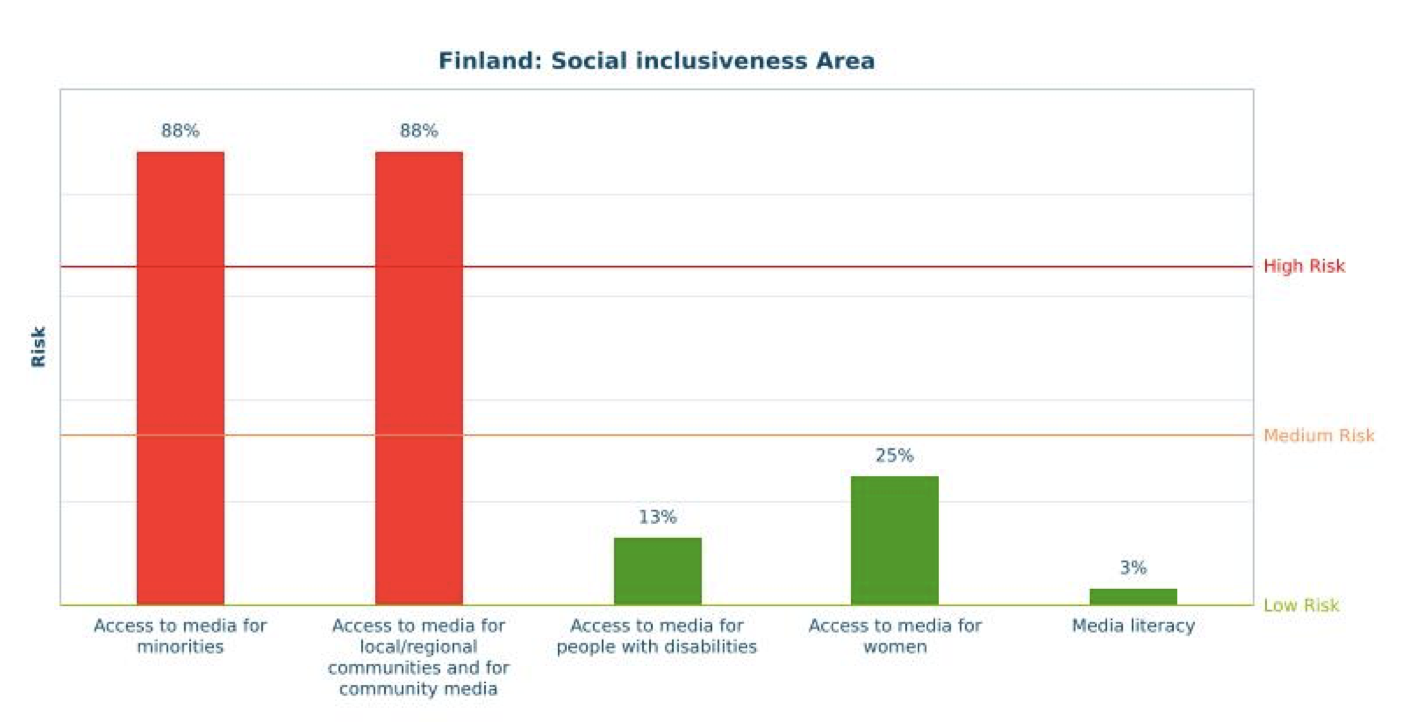

3.4. Social Inclusiveness (43% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

Finland’s risk scores concerning Social Inclusiveness are bipolar: two indicators show very high risk levels and three indicators show low risks. The results may be explained by a liberal policy tradition combined with an unwillingness to regulate media through compelling legislation.

Access to media for minorities has a high 88% risk score. This is due to several factors. First, a law guaranteeing minorities’ access to airtime on PSM does not exist. Second, while minorities do appear in media (both private and public), most minorities are underrepresented. This is largely due to the small size of most minorities in Finland: their purchasing powers are insufficient to support specialized private media, and producing public service content for many, minute audience fragments would be very expensive. Recent research on minorities’ access to media, or their media representations, is not available. The MPM results are partly based on interviews with experts on minority issues and the fact that very few minority media are available, apart from those catering to the legally recognized Swedish and Sámi minorities.

The indicator Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media has a high 88% risk score. The issue here is the Finnish state’s policy of non-interference: protective legislation or subsidy schemes for regional, local, or community media do not exist. Similarly, the PSM is not legally required to maintain regional bureaux or employ people from different regions (regardless, Yle does maintain local bureaux and employs locals – out of its own volition, not due to legal compulsion).

Access to media for people with disabilities indicates a low 13% risk. Legislation and regulatory action make notable efforts to facilitate access to media for people with disabilities. Representatives of two advocacy groups, the Finnish Federation of the Visually Impaired and the Federation of Hard of Hearing, however, find the current measures insufficient (although both commend the progress made in recent years).

Access to media for women has a low 25% risk score. The level is elevated only by two factors. First, women comprise only 22% of the members of Yle’s Administrative Council (but 43 % of the Board of Governors). Second, data from the Global Media Monitoring Project shows that women are underrepresented as news subjects and sources in both traditional and online media. On a positive note, the regulatory framework in support of gender equality is comprehensive.

Indicator on Media literacy shows Finland’s lowest 3% risk score. This score is due to the extensive efforts at increasing media literacy by the Finnish state and civil society. In addition, research shows that basic digital skills are more prevalent among Finns compared to what is the European average.

4. Conclusions

Finland scores notably high risk levels on several indicators. These warning signs do not necessarily imply the need for immediate policy changes. They mostly relate to the lack of regulation: the state has largely chosen to equate media with other businesses and does not impose additional regulation in order to promote plurality. This approach has led to potential problems such as high market concentration, and a scant service to small and disenfranchised audiences. The overall state of media plurality in Finland is fairly good, but some issues should be addressed.

In the context of ‘Basic protection’, Finland should revise its legislation on defamation and blasphemy, and consider whether it is on par with international standards. The effective and uniform implementation of existing freedom of information laws should be ensured.

The high risk scores within the ‘Market plurality’ area warrant further investigation. Introducing new anti-concentration legislation could have severe implications for the financial viability of media businesses. Still, current levels of concentration should be critically examined, especially regarding content plurality.

In terms of ‘Political independence’, further regulation cannot be recommended. Despite the lack of compelling legislation, news media appears to be politically neutral. Instead, the relationship between the public service media Yle and the Finnish state should be considered: how much influence, if any, should the Parliament have over Yle? Legislation and Yle’s organisation should reflect the answer more explicitly than they do now.

In the context of ‘Social inclusiveness’, Finland should consider expanding the current, meagre media subsidy schemes, both in funding and in scope. This could help both local and minority media, the latter of which are especially scarce in Finland. Also the PSM should consider further expanding its services to minorities. As Finland’s minority populations increase their access to media becomes crucial in preventing marginalization and polarization. The PSM should thus be more mindful of their needs.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader |

| Ville | Manninen | Researcher | University of Jyväskylä | X |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Riitta | Ollila | Lecturer, media competition law expert | University of Jyväskylä |

| Reeta | Pöyhtäri | Researcher, media & minorities expert | University of Tampere |

| Petri | Makkonen | Deputy director of Ficora | Finnish Communications Regulatory Authority (Ficora) |

| Mikko | Hoikka | Legal advisor; alliance leader | Finnish Periodical Publishers Association; The Federation of the Finnish Media Industry |

| Marina | Österlund-Karinkanta | Special planner | Yle |

| Juha | Rekola | International ombudsman | Union of Finnish Journalists |

| Heikki | Hellman | Dean (2011-2016), docent | University of Tampere |

Annexe 3. Summary of the stakeholders meeting

The stakeholder meeting was hosted by Yleisradio on 14.11.2016, in Helsinki. Invitations were sent to 26 media industry professionals, officials, scholars, and organisations. The following Yle representatives attended the meeting: Marina Österlund-Karinkanta, Saija Uski, Kirsi-Marja Okkonen, Juha Haaramo, Tuija Aalto, Ismo Silvo, Riitta Pihlajamäki, and Minna Peltomäki. Two other attendees were Juha Rekola from the Union of Finnish Journalists, and the independent researcher Martti Soramäki. A trio of invitees who were unable to attend did comment on the research, post hoc: Hannu Raatikainen (Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority), Kalle Varjola (the Finnish Communications Regulatory Authority), and Mikko Hoikka (representing both the Finnish Periodical Publishers Association, and the Federation of the Finnish Media Industry).

The research’s main results were presented at the meeting, and indicators that showed ‘medium’ or ‘high’ risk were discussed in particular detail. The presentation slides and this report were later sent to all invitees for additional comments. The following summary does not represent a consensus among the commenters, but rather the plurality of (the occasionally discordant) viewpoints offered.

In particular, the area of Political independence evoked lively discussion. Several commenters thought its results represent Finland’s situation as being worse than it really is. Views on Yleisradio were especially varied. Some thought that Yle is less affected by political influences than the results suggest. One commenter suggested that the Parliament’s influence on Yle is not necessarily a bad thing: after all, the corporation is funded by the people – why not have representatives of the people oversee it? Still others saw the political connection both influential and troublesome.

The results within the Social inclusiveness area were widely considered noteworthy, albeit the study’s methodology was questioned: are the definitions of minorities and the evaluations of their situations comparable across nations? One commenter also called for more detailed measuring of media literacy – according to the comment, the current risk score paints an unrealistically positive picture of the situation.

The high risk scores associated with Market plurality area were widely accepted as representative of the reality. One commenter criticized the MPM instrument for neglecting to properly account for PSM’s negative effects on market plurality. According to this view, Yleisradio’s strong market position can restrict the private media market and thus harm the overall media plurality.

The Basic protection area evoked few separate comments. First, it was suggested that attempts at breaking source confidentiality should be considered a risk-increasing factor within the indicator describing journalists’ working conditions. Currently, only successful breaches of source protection increase the risk level. Second, it was pointed out that although criminalization of defamation is harmful, the courts’ current line of interpretation alleviates the law’s chilling effect.

Few comments were made with regards to officials’ practices. First, it was argued that despite its primary focus on financial competition, the Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority’s remit is not in conflict with the goal of media plurality. Second, it was emphasized that the Finnish Communications and Regulatory Authority strictly abides by the freedom of information legislation, even if some (other) officials appear to neglect it.

In general, the MPM study was welcomed as necessary, although some of its definitions, choices of scope, and normative assumptions were criticized. The idealized notion of compelling legislation was considered problematic, because light-touch regulation was also seen as being capable of delivering the desired results. On the other hand, it was admitted that in some countries this focus might be justified, except that evaluating Finland with the same criteria was considered misleading.

—

[1] For more information on MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/