Download the report in .pdf

English

Authors: Urmas Loit and Halliki Harro-Loit

December 2016

1. About the Project

- Overview of the project

The Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) is a research tool that was designed to identify potential risks to media pluralism in the Member States of the European Union. This narrative report has been produced within the framework of the first pan-European implementation of the MPM. The implementation was conducted in 28 EU Member States, Montenegro and Turkey with the support of a grant awarded by the European Union to the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the European University Institute.

- Methodological note

The CMPF cooperated with experienced, independent national researchers to carry out the data collection and to author the narrative reports, except in the cases of Malta and Italy where data collection was carried out centrally by the CMPF team. The research was based on a standardised questionnaire and apposite guidelines that were developed by the CMPF.

In Estonia, the CMPF partnered with Urmas Loit and Halliki Harro-Loit (University of Tartu), who conducted the data collection, commented the variables in the questionnaire, and interviewed relevant experts. The report was reviewed by CMPF staff. Moreover, to ensure accurate and reliable findings, a group of national experts in each country reviewed the answers to particularly evaluative questions (see Annex 2 for the list of experts).

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which represent the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness. The results are based on the assessment of 20 indicators – five per each thematic area:

| Basic Protection | Market Plurality | Political Independence | Social Inclusiveness |

| Protection of freedom of expression | Transparency of media ownership | Political control over media outlets | Access to media for minorities |

| Protection of right to information | Media ownership concentration (horizontal) | Editorial autonomy

|

Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media |

| Journalistic profession, standards and protection | Cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement | Media and democratic electoral process | Access to media for people with disabilities |

| Independence and effectiveness of the media authority | Commercial & owner influence over editorial content | State regulation of resources and support to media sector | Access to media for women

|

| Universal reach of traditional media and access to the Internet | Media viability

|

Independence of PSM governance and funding | Media literacy

|

The results for each area and indicator are presented on a scale from 0% to 100%. Scores between 0 and 33% are considered low risk, 34 to 66% are medium risk, while those between 67 and 100% are high risk. On the level of indicators, scores of 0 were rated 3% and scores of 100 were rated 97% by default, to avoid an assessment of total absence or certainty of risk[1].

Disclaimer: The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the views of the CMPF or the EC, but represents the views of the national country team that carried out the data collection and authored the report.

2. Introduction

Estonia is a small country, both by population and territory. The population is 1.3 million which, by and large, breaks down into two major language groups: Estonian and Russian. The latter group makes up about a third of the total population, and these two groups have totally different media consumption patterns. In this regard, these groups need to be observed separately, especially when tracking reach and share, in order to get a proper idea of the media market.

Estonians tend to watch local Estonian-language channels, whilst Russophones (by and large, this is a generalization) prefer channels that originate in Russia. This refers back to the fact that the Russian-speakers in Estonia (despite their actual nationality) in general represent the massive influx under the Soviet policy of population intermixing[2] (which could be called ‘colonization’[3]). Before World War II, Estonia was a very homogeneous country in ethnic and national terms.[4] This has also had an impact on the integration processes at large in the society, as well as on catering for the Russophones with Estonian media. 26% of those who do not speak Estonian consume only the media from Russia.[5] National daily print media in Russian has disappeared; Russian-language ETV+ had gained a share of only 0.7% by the beginning of 2017, after 16 months of operations.[6]

The economic situation in Estonia has stabilized after a severe collapse in 2009. However, the economy is growing at a very slow pace – the gross domestic product (GDP) of Estonia increased 1.3% in the third quarter of 2016, if compared to the third quarter of the previous year.[7]

The political rule, in principle, has not varied over the last decades. Governments have been formed based on wide coalitions, and they have included liberals, conservatives and social democrats. This is also the current position, even though, during the recent government change (in November, 2016) the Liberal Party (the Reform Party) was replaced by another (the Center Party) – but they are both members of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE). As evaluated after the parliamentary elections in 2011, the situation remains broadly the same: “Ever since independence, the political left has been significantly weak. /…/ Estonia is beginning to resemble a classic left/right dominated party system, where socioeconomic issues of distribution and redistribution form the backbone of the political struggle./…/ Research furthermore shows that, over the years, Estonian parties have come to be increasingly regarded as public organizations rather than private interest groups. Hence, parties in Estonia have gained in public credibility. In combination with a media climate that likewise has changed to actually treating parties as collective organizations driven by ideas and some visions.”[8]

Estonia is a country run on liberal economic principles, in line with the EU. The media market has an oligopolistic character as it is tiny and thus cannot accommodate too many owners. In terms of the advertising expenditure breakdown, after Estonia regained its independence, newspapers were the most influential type of media. This changed in 2010[9], and now television has bypassed the press. The share of the Internet in regard to advertising sales is growing rapidly. Still, due to the small size of the market, the total expenditure for advertising is not large (in 2015 it was 92.6 million EUR[10]). This constricts plurality and quality, especially when content is distributed by multinational companies (such as Google), which usually do not produce content themselves, but earn revenue from redistributing that of others[11].

As to the audiences, the daily time spent on watching TV and listening to radio has not changed in recent years (corresponding, respectively, to around 4h and 3h45).[12] Newspaper circulation figures have been dropping,[13] and traditional newspaper reading has also declined. By 2015, the number of newspapers being read had halved since 2000, both for newspapers read regularly and those read occasionally.[14] However, attention directed to news items has not disappeared, it is only that the traditional channel (print) has been replaced by another (Internet).[15] The aggregated reach (paper and online) has even exhibited a slight growth since 2002.[16] According to Statistics Estonia, almost 60% of the population used the Internet for media and cultural consumption. Among young people (up to 30 years), almost 100% use the Internet and they can be differentiated from each other only by the range of their skills.[17]

3. Results from the data collection: assessment of the risks to media pluralism

The general strengths of the Estonian media policy formulation and implementation include recognising freedom of speech as one of the most important values in a democracy, and good legal regulation relating to access to information.

Since the beginning of the transitional period (after Soviet rule) at the beginning of the 1990s, Estonian media policy has been very liberal and market-oriented: media organizations have enjoyed full freedom of expression. However, since 2009 the Courts have started to argue more about the liability of professional content providers in cases where an individual has suffered severely.

In Estonia, cultural norms are influential and the general approach is rather to avoid legal over-regulation. There is no specific media law enforced in Estonia, except for the Media Services Act (formerly the Broadcasting Act) and the Estonian National Broadcasting Act. Basic values (safeguards) affecting media performance and the related actors have been embedded in the historical discursive institutionalism of the press, defining and enforcing good conduct as part of the national cultural heritage.[18]

While the resources available in this small media market are limited, and original news production is an expensive process, the future of professional journalism is one focal question in media policy that relates to the accessibility of the public to impartial and trustworthy information.

Regarding the social inclusiveness area of the Monitor, Estonia only has some of egal protection mechanisms in place. The laws enabling this kind of inclusiveness stand, either directly or indirectly, as the Constitution of Estonia grants equal rights, regardless the gender, and everyone’s right to publish. In Estonia there are no regulatory instruments to define who may practice journalism.

The Estonian Public Broadcasting Act defines, among the functions of PSB, the transmission of programmes which, within the limits of the possibilities of Public Broadcasting, meet the information needs of all sections of the population, including minorities. However, the tricky part of this provision is “within the limits of the possibilities“, the possibilities do not always appear to be sufficient for the goal. As most minorities in Estonia speak either Russian or Estonian, here is thus no urgent necessity to broadcast in more languages. The potential audiences are too small to be reached in traditional mood over the airwaves. Still, Radio 4[19] of the PSB runs special broadcasts in several minority languages (Georgian, Azerbaijani, Ukrainian, Armenian, Chuvashi, etc.), and the Estonian language channel (Vikerraadio) also carries news in several local dialects. According to the PSB Annual Report for 2015, in 2015 there were 90 hours of programming in other languages, besides Russian, on Radio 4.

Several indicators of MPM exhibit that in the field of local media and community involvement, Estonia formally faces high risk – there are no active support measures for such media and no law addresses this issue. This, of course, is a discussible topic, as Estonia itself, by its territory (45,000 km²) and population (1.3 million), is “a locality”, even on the European scale. Secondly, the country does not go in for awarding subsidies in most areas, including agriculture. From this point of view, the government thus refrains from paying any subsidies to the media, to avoid influencing media performance. On the other hand, local media operate with such small audiences that they need supportive media policies, which do not necessarily need to be pecuniary. In that regard, any supportive measures for local and community media are absent. Instead of investing in an independent regional press, most municipalities tend to issue their own gazettes, resembling journalistic newspapers, which often also sell advertising. The Newspaper Association strongly opposes this feature as it distorts the advertising market and blurs the meaning of “free media”, and the Association has put this question to the state authorities.[20]

Several issues constituting risks for media pluralism are thus derived, either directly or indirectly, from the small size of the overall market. Legal, or even subsidiary measures alone, do not necessarily expand the premisses for media pluralism.

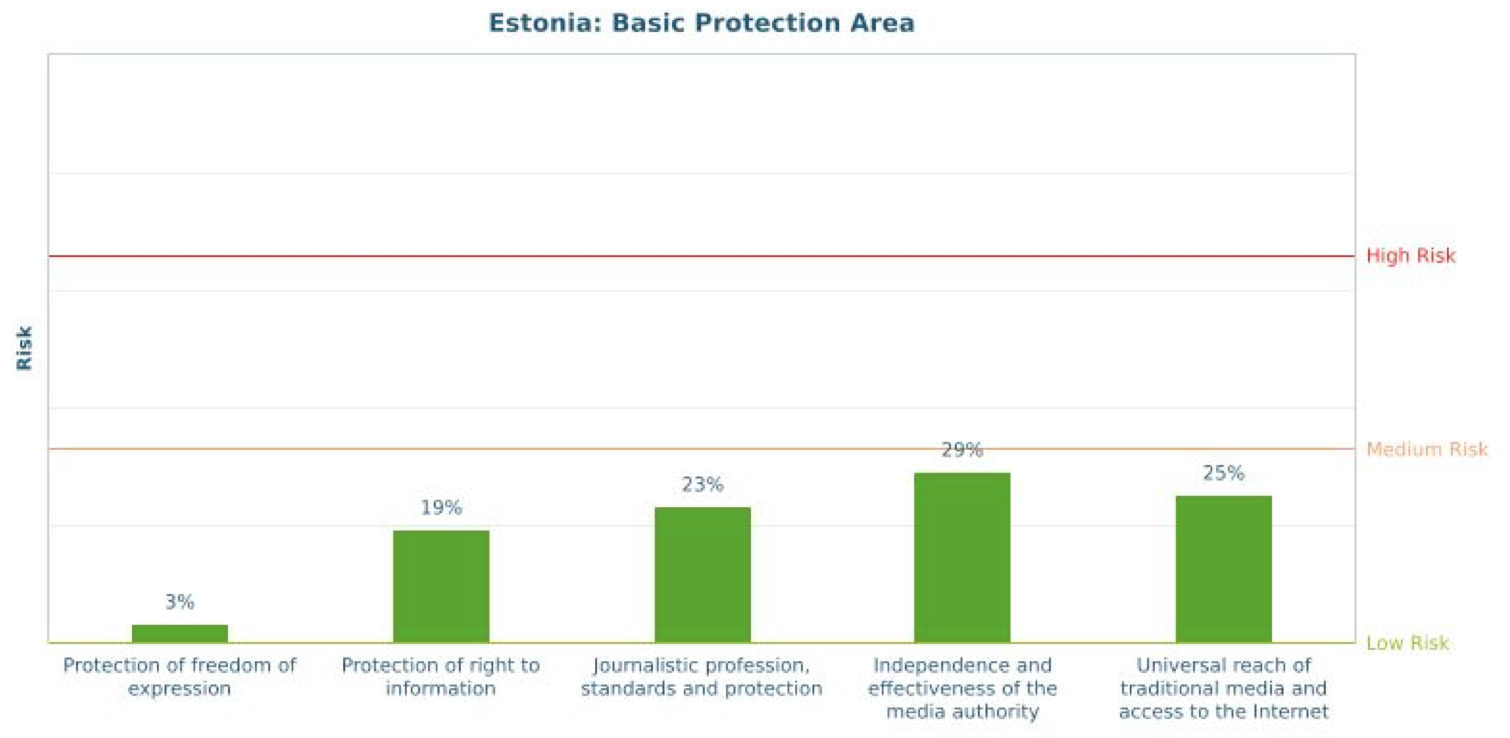

3.1 Basic Protection (20% – low risk)

The Basic Protection indicators represent the regulatory backbone of the media sector in every contemporary democracy. They measure a number of potential areas of risk, including the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to information; the status of journalists in each country, including their protection and ability to work; the independence and effectiveness of the national regulatory bodies that have competence to regulate the media sector; and the reach of traditional media and access to the Internet.

In Estonia, the protection of freedom of expression is both a legal and a cultural feature[21], and in that way it is similar to the Nordic countries. For instance, as in Denmark, with the Mohammed cartoons in Jyllands-Posten, the freedom of expression is assumed to be embedded in the cultural perception of public communication, regardless of the validity of that expression. The small size of the society, together with unfortunate recollections of the country’s experiences in the 20th century, makes any threat against the freedom of expression (incl. press freedom) emergent by means of “whistleblowing” or otherwise. The journalistic profession and its standards function mainly under economic pressure,, which is unlike the situation in several Central and Eastern European countries, and journalists do not face political instrumentalization.

According to the Freedom of the Net Report 2016:

“Estonia continues to be one of the most digitally advanced countries in the world. In June 2015, the European Court of Human Rights upheld an Estonian Supreme Court decision from 2009, stating that content hosts may be held legally liable for third-party comments made on their websites. Since then, major online media publications have removed the functionality for anonymous comments on their websites and have continued active moderation to limit hate speech.”[22]

From the academic viewpoint, Estonia has put in place Court ruling(s)[23] which make a media organization liable for the users’ comments that are added to the journalistic pieces in the publisher’s offer, since part of its business plan does not represent a disproportionate infringement of the freedom of speech but, rather, enables it to cleanse the forum for sound discussion and thus avoids unlawful comments.[24] This case has changed the entire paradigm of net comments in Estonia – folk tend to post comments under registered usernames and the offensive comments are taken down at the earliest possible instant.

The situation with relation to protection of access to information stands at low risk. Like the principle of freedom of speech, accessibility to public information is also granted by an extensive Article in the Constitution. Most public information is accessible online at any time chosen. In other cases, the public authority has to comply with a request for information under the Public Information Act. The media have no exclusive rights in regard to accessing public information.

The state of the journalistic profession, its standards and protection, comprise a low risk for media pluralism issues. In Estonia there are no regulatory instruments to define who may practice journalism. There is no legal necessity for journalists to register themselves with state authorities. Print and online publications need not register, or even inform the authorities, about their intention to release any content. As stated above, the safeguards have been embedded in the historical discursive institutionalism of the press, which defines and enforces good conduct as part of the national cultural heritage. However, the Estonian Journalists’ Union has a low impact on journalism related issues, including the guaranteeing of editorial independence. There are two main reasons for this. The most influential media organisation in Estonia is the Newspaper Association which, in many respects, operates as a non-governmental agency to protect general media freedom and journalistic standards. Nevertheless, it is predominantly an association, representing publishers. The Estonian Journalists’ Union, although it was established in 1919, for a number of active journalists still largely represents the Soviet legacy, and the EJU has failed to abandon this perception. This is combined with the Estonians’ disbelief in trade unions, as such, which also largely tends to call up memories of Soviet institutionalism. No attacks against journalists, either physically or digitally, are known. There is no data available on irregularities in payments but journalists have been reporting on their job insecurity[25]. Protection of journalistic sources is implemented under an Article of the Media Services Act, which, exceptionally, extends to all media.

The print and online publications need not to register or even to inform the authorities about intention to release any content. Consequently, there is no media authority to scrutinize their performance. The only field in which licensing exists is broadcasting (TV and radio, both streaming and on-demand) under the Media Services Act. For a long time, the media policy design and licensing/superintendence of the broadcasters was executed by the Ministry of Culture. Under the testing recommendation by the EU institutions, licensing and superintendence was passed over to Technical Regulation (until recently this was also translated as the ‘Surveillance’) Authority (TRA)) who performs the role of “an independent regulator”. In fact, TRA is a wider agency operating in the administrative area of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications which implements the national economic policy through the improvement of safety, organising the expedient use of limited resources and increasing the reliability of products in the manufacturing environments, industrial equipment, railway and electronic communication. Media surveillance is thus a small section of their overall operations. of which little is reflected in annual reports, and about which there is very little information on the internet. We can thus say[26] that the operations of the TRA in the field of licensing/superintendence of broadcasters are non-transparent. The professional understanding of these matters is only now evolving. The scope of the field often falls between the administrative areas of the two ministries, thus not allowing the implementation of an integral approach.

As to the universal reach of the traditional media and access to the internet, almost the entire population has been covered with an accessible signal for public radio and TV, as well as broadband connection (including the rural areas). The average Internet connection speed in Estonia is 12 Mbps.[27

The Electronic Communications Act sets neutrality in relation to services and technology as a root principle. In practice, no obstruction has been observed. “No questioning of this keystone has ever emerged, presumably for several reasons: free Internet access is considered as a human right, the Internet service providers themselves do not produce content, and the overall market is very small.”[28]

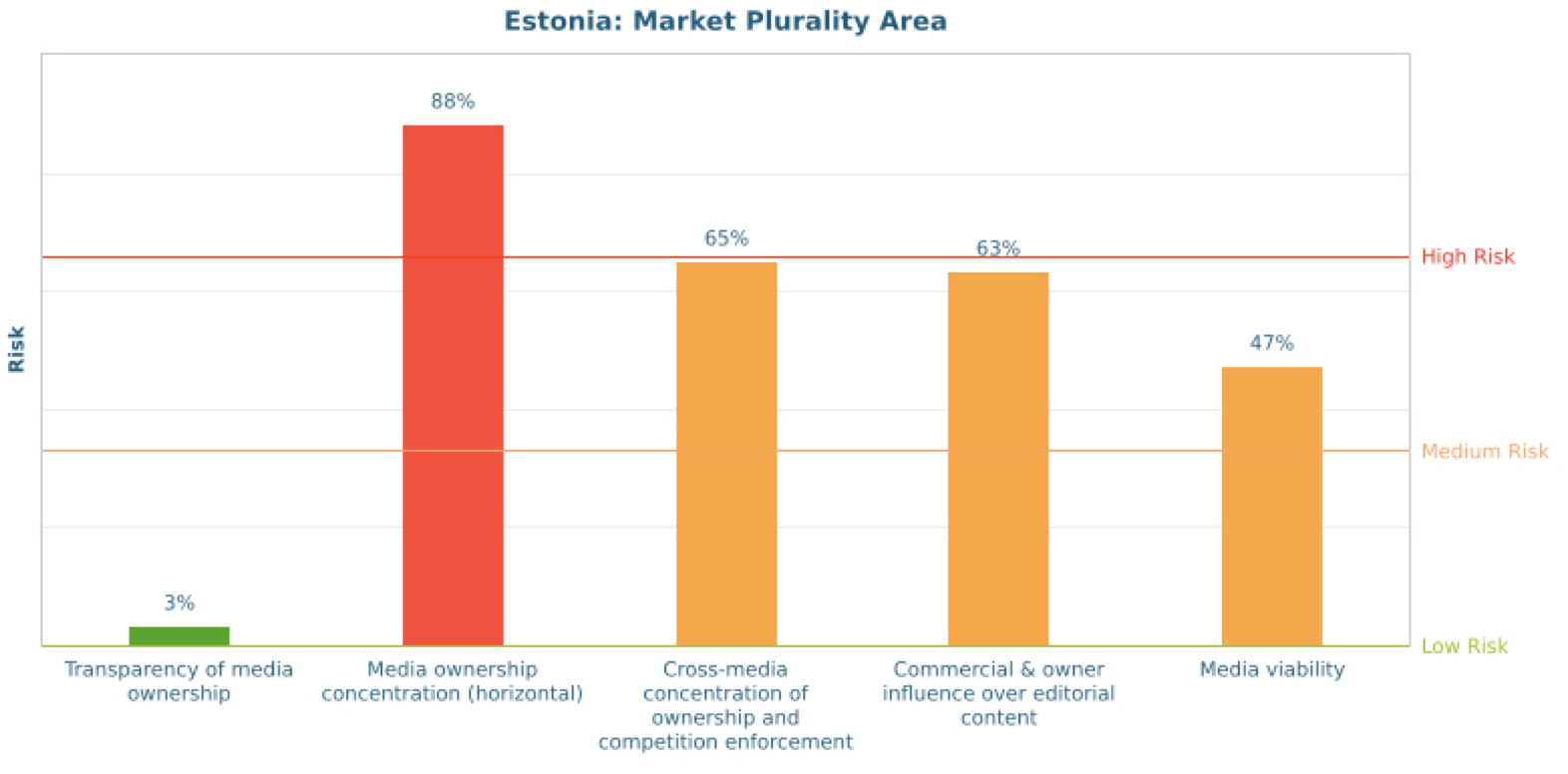

3.2 Market Plurality (53% – medium risk)

The Market Plurality indicators examine the existence and effectiveness of the implementation of transparency and disclosure provisions with regard to media ownership. In addition, they assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards to prevent horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership and the role of competition enforcement and State aid control in protecting media pluralism. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the viability of the media market under examination as well as whether and if so, to what extent commercial forces, including media owners and advertisers, influence editorial decision-making.

The market plurality area shows the highest risks in overall media pluralism, according to the MPM. At least in part, this derives from the small size of the market and its potential audiences which are divided into two diverse groups (Estonian speakers and Russophones). The economic feasibility and profit-earning capacity sets limits on the variety of outlets, especially in regard to restraining the niche ones.

The lowest risk occurs with transparency of media ownership. Media ownership data is available in the Commercial Register and in the Central Register of Securities. The Commercial Code obligates every legal entity to submit certain data[29] about themselves to the Commercial Register, which, under the same law, puts the information in the public domain. Everyone can make e-inquiries to the Register by Internet and can get the data immediately. The data about the shares in the undertakings are kept with the Central Register of Securities.

Two media corporations dominate the whole media market: the Ekspress Group and the Postimees Group. The Bonnier Group owns the national business daily Äripäev. The Postimees Group possesses the biggest daily (Postimees), a television channel (Kanal 2), a group of radio stations (Trio LSL Ltd.), a group of local newspapers and the only news agency, BNS. The Ekspress Group owns two dailies (of which one is a tabloid), two large weeklies and a group of magazines. Radio and television are missing from their portfolio. The other large national television channel (TV3) was owned by MTG until the middle of March, 2017, when it was sold to the US investment company Providence Equity, together with all of MTG’s Baltic operations. Altogether, including the PSB, there are three larger television operators in Estonia.

As the media market is largely divided between two corporations and the public service media, the owners’ influence on the job market is remarkable. In 2013, the Norwegian company, Schibsted, sold Postimees and the new Estonian owner interfered in the appointment of the chief editor which, as far as we know, had never previously been the case. This indicates that a national owner, as such, does not necessarily safeguard the autonomy of the editorial staff. This interference, however, has been episodic, with no further consequences, as it was not tolerated by the professional community nor by the general public.[30]

From the point-of-view of media viability, concentration of media ownership is somewhat inevitable in a tiny market. Estonia had a daily newspaper market with seven titles in the late 1990’s – all of which were running at a loss. The oligopolistic system, with two main daily papers and two major television channels and other very small occurrences enables media businesses to operate without ruinous losses. In this regard, the MPM tool’s measurement cannot be applied here mechanically, as deficit ventures cannot produce pluralism of content, at least in the long run. In addition, there would be little audience for such a variety, and either. Independent operation or the public service media would minimize the hazard by distorting or narrowing the reality of the coverage in the media.

Media viability, with regard to advertising turnover, shows endurance primarily in the field of online media (In 2015 vs. 2014 online advertising turnover grew by 16.3%), while other types of media (print, television, radio) have experienced a relative standstill, and their share in the total volume of the advertising turnover is slowly fading. The largest portion of the total advertising income went to television (27.4%). Online advertising is now in the third position (18.6%), just after newspapers (19.3%).[31] To a great extent, the online business is run by the newspaper publishers, thus, in aggregate, for those particular companies it tends to be a reallocation of the sources of income, rather than new income. Radio shows relative endurance in all measurable counts (audience share, listening time, trust in, percentage in the total breakdown of the advertising turnover, etc.) and proves to be more viable than the average in Europe. However, the absolute figure for the entire advertising market is unsound: 92.6 million Euros.

The State offers no subsidies to media organizations, other than PSM, with the exception of cultural popular science, and children’s outlets that are published by a state-established foundation (SA Kultuurileht). There is no evidence of indirect subsidies for media, including “state advertising” in the form in which it is known in many parts of Europe, expressing favouritism towards certain outlets. There are as yet no visible signs of media organizations, under the shifting business models in the development of initiatives,that would ensure access to alternative sources of revenue other than the traditional revenue streams.

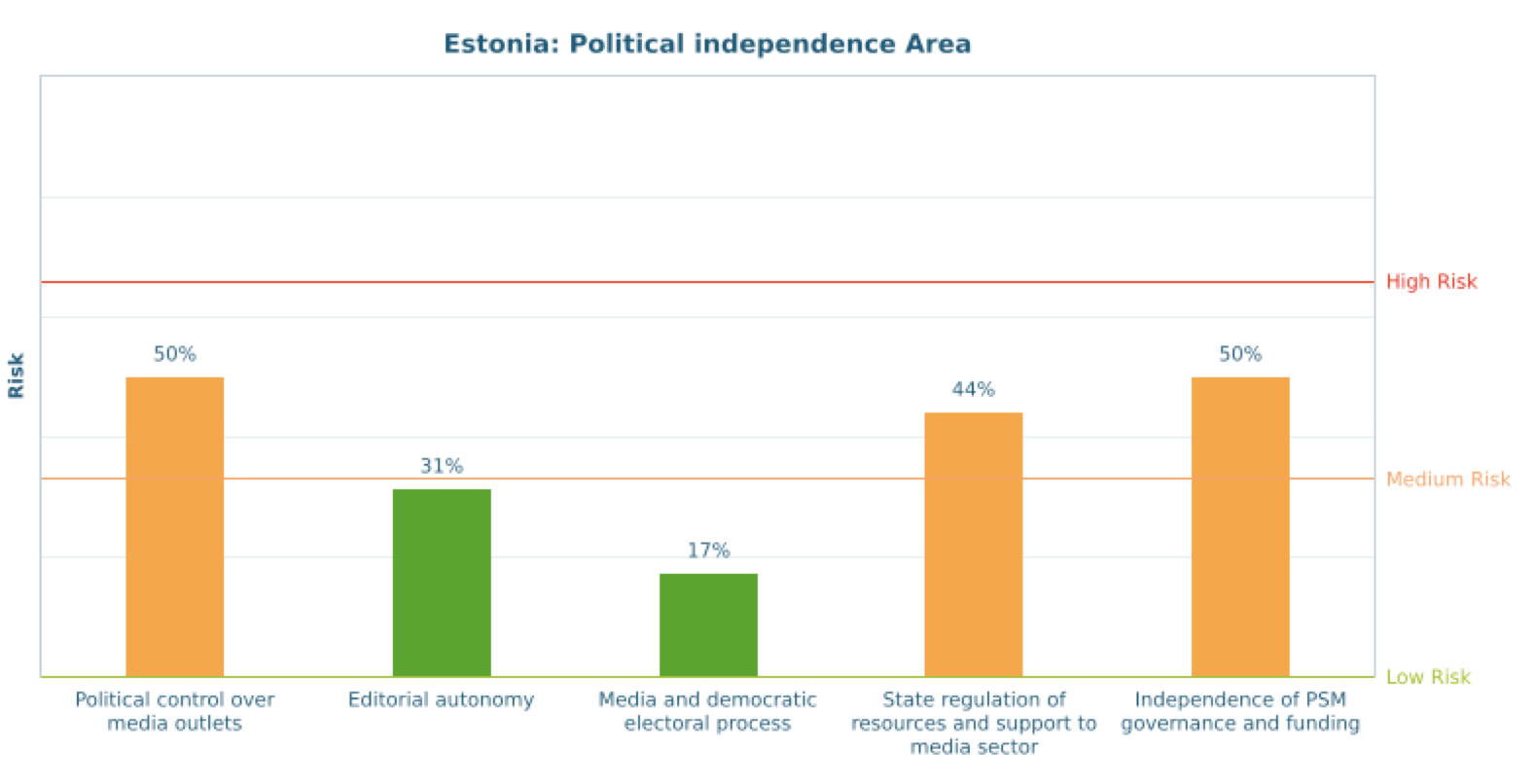

3.3 Political Independence (38% – medium risk)

The Political Independence indicators assess the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over the media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks. They are also concerned with the existence and effectiveness of self-regulation in ensuring editorial independence. Moreover, they seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) on the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

There is no direct political control of national media outlets[32]. The medium risk in scoring derives from the fact that there are few legal safeguards written into the laws. This is another peculiarity in the Estonian media policy – the safeguards have been embedded in a historical discursive institutionalism of the press that defines and enforces good conduct as part of the national cultural heritage.[33] Some local news outlets (municipal gazettes issued by municipal governments) can be characterized as being politically influenced. This includes the municipal newspapers of the capital city (Tallinn), and the nationally distributed Tallinn TV, also run by the city government, which have often been politically engaged against the national government, as the majority rule in the capital city has been executed by a sole party (the Centrist Party) which, so far, on the national level, has been in opposition.[34]

The majority of media organizations value editorial autonomy. According to the results of the survey “Worlds of Journalism”, about 70-80% journalists believe they are autonomous in different aspects of reporting. The MPM indicator scores low risk here. The Code of Ethics of the Estonian Press promotes editorial independence (Section 2). Most of the Estonian newspapers and TV channels have accepted the Code of Ethics. Even though the Code was adopted 20 years ago, it can still be adaptable for the online media too. Only one national daily, Äripäev (Business Day), has its own code of ethics, due to the specific nature of its field of coverage. This code of ethics also focuses on independence and autonomy, even more that the general code does.

The national Code is enforced by two press councils, of which one is affiliated to the Newspaper Association and the other to the Journalists’ Union and the Association of Media Educators. This richesse of press councils derives from a conflict 15 years ago, but today it provides competitive viewpoints and, as a result, improves the self-regulatory discourse. The working self-regulation has prevented the State from interfering with media performance, even when it would have been eligible to do so, for example, to protect the public’s interest, or to protect the rights of an individual.

The indicator on ‘Media and the democratic electoral process scores the lowest risk in this area (17%). The media usually cover elections in a balanced way. Under the law, the broadcasting organizations are obliged to provide airtime to political parties on an equal basis. There is some more detailed regulation for the PSM but, as a rule, a media organization sets the rules itself. Print and online media base it on self-regulation.

The public broadcasting (PSM) is financed from the state budget and no advertising is allowed to be broadcast. It has been a problem for years that financing for the PSM is insufficient and that it is not predictable for a longer period of time, as it is allocated annually. This could even be perceived as being political pressure on the PSM. Other media, with the exception of some cultural papers/magazines, are not financed by the state. There is also no large-scale state advertising to politically influence the media. There are some public announcement campaigns that are set up to grab the general public’s attention on nationally important issues (traffic safety, etc.) the media plans of which are made under the procedures envisaged by the Public Procurement Act.[35] There is no evidence to prove that this system may have been misused to influence the media’s performance for political purposes.

The PSM council is appointed by the parliament and consists of one representative of each political party with representation in parliament, and four members from among the acknowledged experts in Public Broadcasting. In 2016, in total, there were 10 members of the Council. Under the law, the Council operates independently.

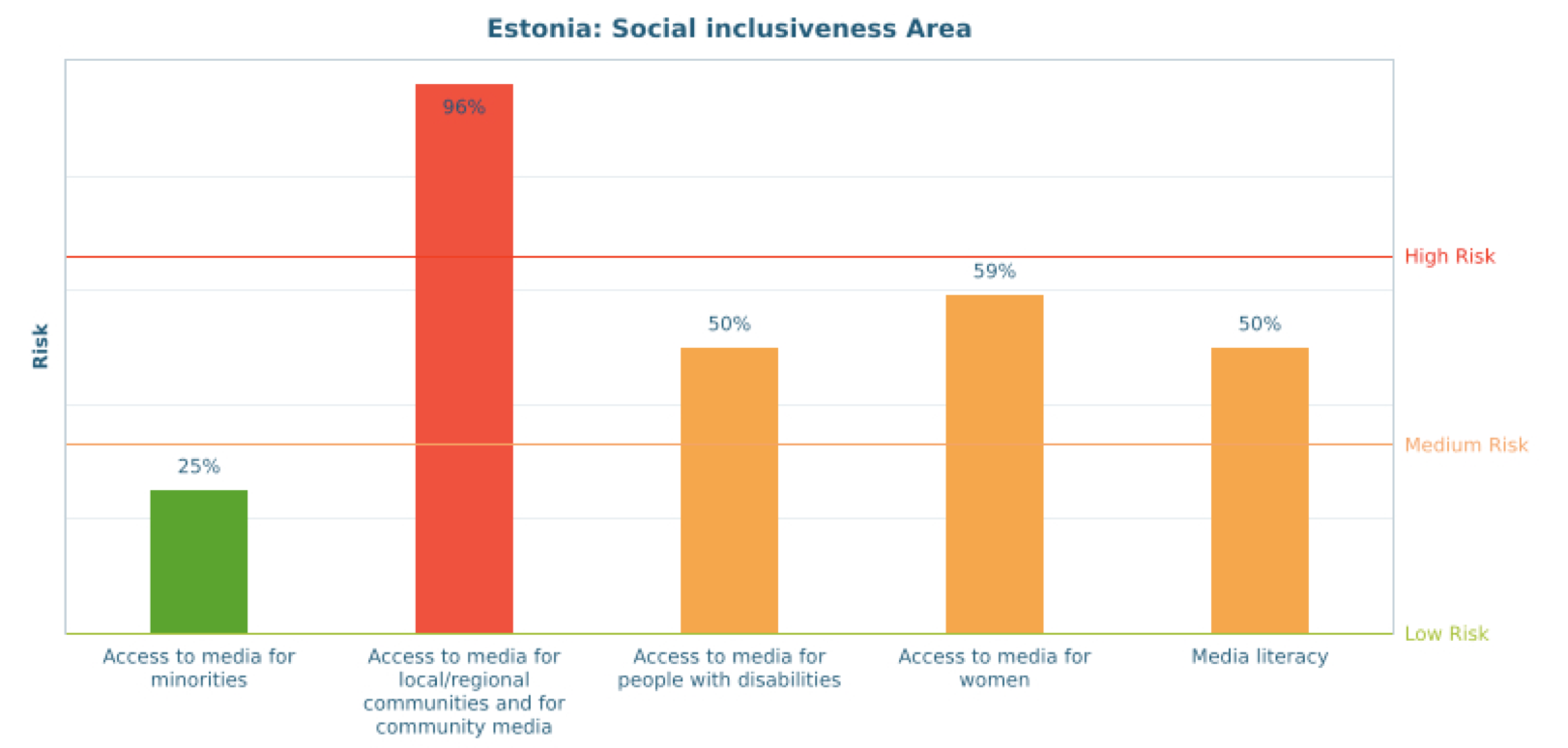

3.4 Social Inclusiveness (56% – medium risk)

The Social Inclusiveness indicators are concerned with access to media by various groups in society. The indicators assess regulatory and policy safeguards for community media, and for access to media by minorities, local and regional communities, women and people with disabilities. In addition to access to media by specific groups, the media literacy context is important for the state of media pluralism. The Social Inclusiveness area therefore also examines the country’s media literacy environment, as well as the digital skills of the overall population.

In relation to the social inclusiveness area of the Monitor, Estonia has only some of the legal protection mechanisms in place. The laws that enable this type of inclusiveness, stand, either directly or indirectly, as the Constitution of Estonia grants equal rights regardless of gender, and everyone has the right to publish.

The indicator on the Access to media for minorities scores low risk (25%). The Estonian Public Broadcasting Act defines, among the functions of the PSB, the transmission of programmes which, within the limits of the possibilities of Public Broadcasting, meet the information needs of all sectors of the population, including minorities. This issue has been elaborated above (Section 3). Considering that a large proportion of Russophones – who make up around a quarter of the entire population – prefer to follow the media from Russia, especially TV, the overall standing is not too bad. This generalization, of course, would not be fully true, as the media consumption patterns for Russophones are fragmented, since some of them follow the media in a more transnational way than others.[36] The PSB’s Radio 4 is the most listened to radio station by Russophones. Lately, in 2015, a new TV channel (ETV+) was launched in Russian by the PSB. This still needs to reach the audiences but, at the same time, it illustrates the media preferences of Russophones – the share of the Russia-originated PBK is some 10 times higher than that of ETV+.[37]

The indicator on the Access to media for local/regional communities and for community media scores very high risk (96%). The regional and local media in Estonia is meagre. The country itself is like a locality (a suburb of a larger city), both by territory and population (1.3 million), which affects the sustainability of local media. The local newspapers, even though they are the most vital branch of local media, are considerably weaker than the national print media, both economically and journalistically. For instance, in 2015 the sales revenue of local newspapers was just 18% of the total industry volume.[38] The newspapers depend greatly on personal relationships within the small communities and are, thus, less sharp and investigative.[39] Over time, the number of local radio stations has decreased to five, of which only two provide a full journalistic programme – others only carry some of its features. Local terrestrial television ceased to exist after the switch over to digital broadcasting, due to the remaking of the national radio frequency plan, which allocated no multiplexes to local broadcasting. Few TV programmes exist in small local networks, about which not much is known. The foremost reason for lacking plurality in local media is the absence of resources (both financial and labour) and small local populations.

The indicator on the Access to media for people with disabilities scores medium risk (50%). The rules about catering for the disabled audiences with hearing and visual impairments exist (e.g., by the Media Services Act), but implementation is poor. Only the PSB provides subtitles for selected programme reruns and enables a synthesized voiceover for the TV output. Private media does not do this.. As the experts for the MPM from the federations for the deaf and the blind have evaluated in this respect The general picture is thus chaotic and insufficient, but might be better if there were at least reruns and catch-up services (medium risk). Voice descriptions are absent both in PSB and online services. Even though there is a daily newscast in sign language on ETV2, the experts in this field deeply miss Estonian subtitles and sign-language translations in daily topical broadcasts on politics and current issues.

The indicator on Access to media for women scores medium risk (59%). As to the gender equality indicators, we can say that the law ensures the equal treatment of men and women and the promotion of the equality of men and women as a fundamental human right and for the public good in all areas of social life. Still, as the Gender Equality and Equal Treatment Commissioner, Liisa Pakosta, put it in an interview for the MPM: “The gender-based segregation among the employees of media organisations, and also the probable horizontal segregation and the probable gender pay gap are not insistent against the general background in Estonia.” As to the employment of women, the percentage of female journalism workers is, in general, somewhat higher than that of males (58.4% of women).[40] Assessing, for example, the management of the PSB, all of the members of the Board are men, but the heads of particular channels are women (seven out of eight). The guidelines for balanced and neutral programming of the PSB include gender balance requirements in regard to the output.

The indicator on Media literacy scores medium risk (50%). There is no strategic policy document on media literacy in Estonia. Media literacy is included in the national curriculum of formal education as a cross-curricular theme, “Information environment”, that should be applied at all school levels. In addition, two courses in upper high school (“Media and its influence” and “Practical Estonian language 2, 35 lessons each) are mandatory. Schools may include voluntary media courses in the school’s curriculum. There are some NGOs to hold short workshops for the interested children and youth all over Estonia.

4. Conclusions

Estonia has a stable and well-consolidated democracy where the freedom of speech and freedom of expression is strongly protected, both legally and culturally. The small size of the country enables it to be flexible in terms of innovation, new technologies, etc., but also includes risks: few choices, e.g., media concentration, comparatively few jobs for journalists, a small number of experts, weak local media. The latter constitutes the highest risk in relation to Estonia.

The MPM tool revealed comparatively low risk in the basic protection area, as well as in the indicators for transparency of media ownership, editorial autonomy, media within the democratic electoral process, and access to media for minorities.

As iterated, the Estonian media policy includes a distinction – the safeguards have been embedded in the historical discursive institutionalism of the press, which defines and enforces good conduct as part of the national cultural heritage. Not all the safeguards have thus been written into laws, as these are self-evident and are obeyed without objection by all players. To keep it and to advance value clarification, the media industry would need special and active support from the public, the State, and the profession itself. Several challenges face Estonian media performance — such as the decreasing financial resources for journalistic content production, recent uncommon practices of personnel management (owners being involved in this, which may endanger the editorial autonomy, although this occurred after the current MPM check-up), weak local radio, and a generally increasing imbalance between the capital and the regions, the increasing hybridization of news media and infotainment with commercial text, etc. These issues ought to be put on the political agenda.

Given that, so far, no media policy as a public agreement has ever been formulated, and the industry has been happy that the State does not interfere, the new challenges, however, would empower the composition of a national news media and communication strategy document with which to face the global changes in the field. These ideas are in the very initial stages, but they intend to provide an elaborate policy for retaining professional journalists as information processors and as society’s watchdogs. Involving various players (media educators, the State, industry, cultural institutions), the plan is to institute a foundation providing grants for individual journalists in order to promote personal development and, thus, to advance the quality of journalistic output.

Annexe 1. Country Team

The Country team is composed of one or more national researchers that carried out the data collection and authored the country report.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution | MPM2016 CT Leader |

| Halliki | Harro-Loit | Professor in journalism | University of Tartu | ü |

| Urmas | Loit | Lecturer in journalism | University of Tartu |

Annexe 2. Group of Experts

The Group of Experts is composed of specialists with a substantial knowledge and experience in the field of media. The role of the Group of Experts was to review especially sensitive/subjective evaluations drafted by the Country Team in order to maximize the objectivity of the replies given, ensuring the accuracy of the final results.

| First name | Last name | Position | Institution |

| Kadri | Ugur | Lecturer in interpersonal and educational communication | University of Tartu |

| Triin | Vihalemm | Professor in Communication | University of Tartu |

| Judith | Strömpl | Associate Professor in Social Policy | University of Tartu |

| Liisa | Pakosta | Gender Equality and Equal Treatment

Commissioner |

Independent high official |

| Tiit | Papp | Chairman | Estonian Association of the Deaf |

| Jakob | Rosin | Board member | Estonian Federation of the Blind |

| Monica | Lõvi | Board member | Estonian Federation of the Blind |

| Helle | Tiikmaa | Vice Chair of the Board | Estonian Association of Journalists |

| Ragne | Kõuts-Klemm | Lecturer in Sociology of Journalism | University of Tartu |

| Mati | Kaalep | Adviser of AV Affairs | Ministry of Culture |

—

[1] For more information on the MPM methodology, see the CMPF report “Monitoring Media Pluralism in Europe: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor 2016 in EU-28, Montenegro and Turkey”, https://monitor.cmpf.eui.eu/

[2] Center for International Development and Conflict Management. (2006). Assessment for Russians in Estonia. Minorities At Risk Project. University of Maryland: College Park. Retrieved from https://www.mar.umd.edu/assessment.asp?groupId=36601 (10 Dec 2016).

[3] Kalekin-Fishman, D., Pitkanen, P. (Eds.) (2007). Multiple Citizenship as a Challenge to European Nation-States. Sense Publishers: Rotterdam/Taipei. p 215.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Leppik, M., Vihalemm, T. (2017). Venekeelse elanikkonna hargmaisus ja meediakasutus. [Transnationalism and media usage of the Russophone population] In P.Vihalemm et al (Eds) Eesti ühiskond kiirenevas ajas. Uuringu Mina. Maailm. Meedia“ 2002–2014 tulemused [Estonian society in accelerating time: change in habitation of Estonia in 2002-2014 based on results of the study Me. World. Media],Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, pp. 591-619.

[6] Data by Kantar Emor January 2017.

[7] Statistics Estonia. (2016). In the 3rd quarter, economic growth was driven by transportation, trade and the energy sector. News release no 137 of 9 Dec 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.stat.ee/news-release-2016-137

[8] Bennich-Björkman, L. (2011). Estonian Elections. Stability and consensus. In: Balticworlds.com. Retrieved from: https://balticworlds.com/stability-and-consensus/ (10 Dec 2016).

[9] Loit, U., & Siibak. A. (2013). Mapping digital media: Estonia. A report by the Open Society Foundations. Retrieved from https://www.opensocietyfoundations. org/sites/default/files/mapping-digital-media-estonia-20130903.pdf (accessed 5 Jan 2017), p. 67.

[10] Data by Kantar Emor (released 5 May 2016).

[11] See, e.g., Luik, H.H. (2015). Ajakirjanduse kuusnurk [Hexagon for journalism]. In Loit, U. (Ed.) Akadeemiline ajakirjandusharidus 60 [Academic journalism education 60], vol. 2, p. 16; or Kõuts, R. (2016). Maakonnaleht ja omavalitsuse infoleht: “kõlvatu” konkurents?” [County newspaper and the municipal gazette: an unfair competition?]. Postimees. 26 Oct.

[12] Retrieved from the data by Kantar Emor.

[13] Based on data from the Estonian Newspaper Association, www.eall.ee.

[14] Based on data collected by Kantar Emor.

[15] Vihalemm, P. & R. Kõuts-Klemm. (2017). Meediakasutuse muutumine: internetiajastu saabumine [Change in media consumption: arrival of the internet era]. In P. Vihalemm et al. (Eds). Eesti ühiskond kiirenevas ajas: elaviku muutumine Eestis 2002-2014 Mina. Maailm. Meedia tulemuste põhjal [Estonian society in accelerating time: change in the habitation of Estonia in 2002-2014 based on the results of the study Me. World. Media], Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ragne Kõuts-Klemm, et al. (2017). Internetikasutus ja sotsiaalmeedia kasutus [Usage of the internet and social media]. In P. Vihalemm et al. (Eds). Eesti ühiskond kiirenevas ajas: elaviku muutumine Eestis 2002-2014 Mina. Maailm. Meedia tulemuste põhjal [Estonian society in accelerating time: change in the habitation of Estonia in 2002-2014 based on the results of the study Me. World. Media], Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.

[18] Cf. Harro-Loit, H.; Loit, U. (2014). The Role of Professional Journalism in the ‘Small’ Estonian Democracy. In: Psychogiopoulou, E. (Ed.). Media Policies Revisited. The Challenge for Media Freedom and Independence (206−219). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 213-218.

[19] The most listened to radio channel among the Russophones.

[20] Postimees. (2016). Juhtkiri: võimu propaganda pole ajakirjandus. [Editorial: propaganda of powers is not journalism] Postimees, 22 Oct.

[21] As referred to in Footnote 18, the basic values (safeguards) affecting media performance, and the related actors, have been embedded in historical discursive institutionalism of the press, which defines and enforces good conduct as part of the national cultural heritage.

[22] https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2016/estonia

[23] The Ruling of the Supreme Court of Estonia in the case V. Leedo vs. Delfi , no 3-2-1-43-09 (10 June 2009); and the Ruling by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights on the case Delfi AS vs. Estonia, no 64669/09 (16 June 2015).

[24] Nõmper, A., Käerdi, M. (2015). Sõnavabadusest ja vihakõnest Leedo vs. Delfi juhtumi valguses [Freedom of expression and hate speech in the light of the case Leedo vs. Delfi], in Blog of the Estonian Bar Association. Available at https://www.advokatuur.ee/est/blogi.n/sonavabadusest-ja-vihakonest-leedo-vs–delfi-juhtumi-valguses (accessed in 15 March 2017).

[25] Niinepuu, J. (2012). Ajakirjanike autonoomiat mõjutavad tegurid. [Factors affecting the Autonomy of Estonian journalists], Master’s Thesis, University of Tartu.

[26] In part, this is based on the personal observations of the authors in regard of the current report.

[27] Data from the content distribution management company Akamai

[28] Harro-Loit, H.; Loit, U. (2011). Mediadem Case study report. Does media policy promote media freedom and independence? The case of Estonia. Available at https://www.mediadem.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Estonia.pdf (accessed 15 March 2017).

[29] E.g., business name, registration code, board members, location, contacts, foundation articles, annual reports, bankruptcy facts, etc.

[30] See, e.g., Eilat, T. (2015). Rõtov Postimehe olukorrast: sellist fopaad poleks Linnamäelt oodanud. [Rõtov: Would not have expected such a faux pas from Linnamäe], News portal of the PSM, 4 Oct, available at https://uudised.err.ee/v/majandus/775c8898-e562-4ebd-a8af-92951fb0f4e3/rotov-postimehe-olukorrast-sellist-fopaad-poleks-linnamaelt-oodanud (accessed 25 Jan 2017)

[31] Data of 2015 by Kantar Emor. https://www.emor.ee/eesti-meediareklaamituru-2015-aasta-kaive-oli-9264-miljonit-eurot/ (retrieved 25 Jan 2017).

[32] https://www.worldsofjournalism.org/

[33] Cf. Harro-Loit, H.; Loit, U. (2014). The Role of Professional Journalism in the ‘Small’ Estonian Democracy. In: Psychogiopoulou, E. (Ed.). Media Policies Revisited. The Challenge for Media Freedom and Independence (206−219). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 213-218.

[34] Which is expected to end, as, at the end of 2016, a new Chair was elected for the Party to replace the previous one, and the Party entered the coalition in the parliament and holds the post of the Premier.

[35] Media buying under the Public Procurement Act definitely provides traceable data, such as the transparency of public spending. However, the media campaigns, as a rule, are carried out on a small-scale and are not recorded in any consolidated register. As data collection over such a range, from all state institutions’ financial reports does not fit into the scope of the MPM, it has not been carried out during this research, and the indicator on “state advertising being distributed to media outlets based on fair and transparent rules” has been tagged as “no data”. Consequently, the indicator on State regulation of resources and support for the media sector scores a medium risk.

[36] Leppik, M., Vihalemm, T. (2017). Venekeelse elanikkonna hargmaisus ja meediakasutus. [Transnationalism and media usage of the Russophone population] In P.Vihalemm et al (Eds) Eesti ühiskond kiirenevas ajas. Uuringu „Mina. Maailm. Meedia“ 2002–2014 tulemused [Estonian society in accelerating time: change in habitation of Estonia in 2002-2014 based on results of the study Me. World. Media], Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, pp. 591-619.

[37] Data of December 2016 by Kantar Emor. Shares of the average audience.

[38] Calculated upon data from the Estonian Newspaper Association.

[39] Schmidt, A. (2011). Eesti neliteist maakonnalehte aastal 2011. [Fourteen county newspapers of Estonia in 2011], Master’s thesis. Tartu: University of Tartu.

[40] Harro-Loit, H., Lauk, E. (2016). Journalists in Estonia. In Worlds of Journalism Study. Retrieved from https://www.worldsofjournalism.org/country-reports/ (accessed 15 March 2007).